LIFE AT 104 MILLWOOD

ROAD

The 1930s saw North America

in a very deep economic depression. In Canada, the situation was made even

worse by drought in Saskatchewan which ruined many farmers. There was a great

movement of men across this country, riding the rails in search of employment.

It was a very difficult time for many people to find jobs. This bleak economic

situation impacted any young person about to enter the workforce. Rindo had

finished high school in Niagara Falls and Italo, Henry and Lindo who were

attending North Toronto Collegiate would soon be graduating. The jobs they were

able to get for themselves in the 1930s included short order cook, butcher’s

assistant, clerk, all pretty low paying jobs but they were lucky to get them.

The possibility of higher education at this time was out of the question

because of financial constraints. There was no program of student loans or

financial support for students and putting yourself into debt was not an

option. We were fortunate in that Libero didn’t lose his employment. I remember

that his salary was $100.00 a month supplemented by a free dwelling. This was

barely enough to feed and clothe our large family. Our shoes had holes in the

soles and we extended their lives by making newspaper insoles. We bought navy

beans by the sack and spaghetti by the case. At harvest time, many bushels of

grapes were delivered to the house. Libero converted these grapes to fill 2

barrels with homemade wine.

The Sauro

family 1934, Toronto

Olindo, Italo,

Alberindo. Henry,

Livio, Libero,

Elvino, Clementina, Sylvia, Silvio

Libero always cultivated a

large garden and continued to do so all his life. He grew beans, corn, tomatoes

and many other vegetables as well as flowers which graced the church every

Sunday during the season. We also had peach trees and an apple tree and a grape

arbour in the backyard.

This

photo was taken from the third floor window. The rows of vegetables and flowers

are all neatly arranged at the beginning of the growing season. Livio broke his

arm after falling from the apple tree at the back of the yard.

Elvino, Cinna,

Sylvia, and Silvio pretending to be gardeners.

In the winter, our basement

boasted jars and jars of tomatoes, green beans, peaches and pears.

In

1936, on June 16, Roma who has always been known by her pet name Cinna, was

born.

Elvino,

Clementina with Roma, Sylvia, Silvio,

or Cheek,

Cinna, Picca, Toom as we were called.

We were never addressed by our given names. Alberindo was Nolli, Italo – Pezeek, Henry - Zicooch, Lindo was Ponj, and Livio, Franveleek. The older boys were also given very derogatory nicknames such as goat and big pig. We all rejected these names when we could except for Cinna who has clung to hers and has actually legalized.

Clementina was gentle and kind but she, like the rest of us, was ruled by Libero. He was despotic. His word was law and there was no compromise. Transgressions, however mild were dealt with severely with a length of rubber hose. Many times, I was black and blue about my rear end and legs from these beatings. On one occasion when I had been responsible for setting the table, I neglected to go down to the wine cellar, (a place I feared for its darkness and cobwebs), to fill the pitcher with wine from the barrel and put it before my father’s place at the table. When my father sat down, I was commanded to right my wrong. I guess my execution was less than perfect because somehow, wine had gotten onto the base of the pitcher so that when it was placed on the white tablecloth, it left a red ring. The command to “Go get the hose,” was barked at me. Yes, you even had to fetch the instrument of torture, and I was whipped and sent to bed with no supper.

When Clemmie was responsible for disciplining us, she was obliged to use the hose but she never really hurt us. She did, however, make us lick soap if we said bad words like ‘darn’ or ‘heck’. When we fought with each other she made us kiss and make up. That was a terrible punishment.

Libero controlled all the money. Clemmie never had more than a few pennies in her purse. When she needed anything, she was required to ask him and hope for his approval. He would probably make the purchase himself, depriving her of making a choice for herself. He did the shopping and the cooking. When Clemmie complained of a painful back from bending over the washtubs in the basement, instead of moving the washer upstairs as she asked, he took over the laundry as well. He was neither a good cook nor launderer.

Recreation was all self-made. Baseball was a popular sport among the boys in the family. We had a narrow dirt driveway at the end of which was a tin garage. We played baseball in this narrow space with a catcher, 1 or 2 batters, a pitcher and maybe a fielder. If the catcher missed, there was a loud bang of the ball hitting the tin garage. We would try to hit the ball straight down the driveway but it would often hit the wall of our neighbour’s house and on a few occasions even their basement windows. They eventually covered the windows with chicken wire to protect them. We young ones honed our baseball skills in the driveway. Italo taught me to pitch a curve ball there. The older boys were organized into a neighbourhood team. Under Hank’s leadership and organization skills, this team grew to a neighbourhood league involving teams from neighbouring streets. These games were played in the evening in the schoolyard just up our street and they sometimes even attracted spectators. On occasion, I was allowed to be the official scorekeeper.

Davisville Park was near our house. In the summer, it offered a shallow wading pool for us younger ones, tennis courts and a ball diamond. In the winter, two rinks were kept well flooded and cleared. One was a hockey cushion and the other was for pleasure skating.

I don’t remember that our parents ever played any games with us although my father used to play only with Cinna a card game called Scopa. We had a crokenole board and I remember the odd game of rummy.

When the older boys were working, before the war, they spent their money on jazz records. They took a corner of the cellar that was divided off, painted the concrete floor green with a big orange circle in the centre and called it The Jive Room. It housed a record player and their growing collection of records which of course were the old thick black 78rpm variety – one 3-minute piece to a side. This music, which Libero called ‘this blessed junk’ was confined to the cellar. Needless to say, he had no taste for this sound but he was powerless to stop it against grown-up sons.

When the family arrived in

Toronto, Alberindo had already finished high school in Niagara Falls. The other

children settled in to the local schools; Italo, Henry and Olindo to finish

high school at North Toronto Collegiate where Italo was able to shine with his

singing ability and Henry developed his journalistic skills by working on the

school paper. Livio went to Davisville Public School. Silvio started Kindergarten there and Elvino

and I were not school age yet.

Teaching methods were quite

different than they are now. Our desks with attached seats were screwed to the

floor in rows. We were required to sit up straight with our hands folded in

front of us on the desktop. You were never allowed to speak unless called upon

to do so.

At recess, the boys and girls

had separate yards. The girls played volleyball, hopscotch, tag and various

active games until the bell rang. The boys could play baseball or kick a soccer

ball around or throw a ball against the wall. We lined up according to our

classroom and were directed in, military fashion by the presiding teacher

tapping the bell clapper in a marching rhythm.

Elvino, Silvio and I went to

North Toronto Collegiate after Davisville Public School while Livio went to

Northern Vocational School. In time,

Cinna started there too. What was life

like for this large family during the 1930s and 1940s? I can only tell you what I remember of it and

I am not good at remembrances.

Food or the lack thereof

figures prominently in my memory. I don’t remember my parents ever getting up

before we were off to school. For a time, Italo took it upon himself to provide

the breakfast of porridge onto which we could pour a little milk. This was a

treat. We had 2 quarts of milk delivered every day for all those people. It was

mostly used in tea and coffee for the big people and for porridge in the

morning. I don’t remember ever drinking a glass of milk.

When we were in public school

everyone went home for lunch. There was an hour-and-a-half interval which

allowed even those who lived the greatest distance to go home. There was no one

who had lunch at school. Our lunch consisted of 3 pieces of dry bread and a

little piece of orange cheddar cheese. We had our bread delivered every other

day or maybe even 3 times a week from an Italian bakery. Our breadbox consisted

of 2 shelves that my father had lined with tin. The fresh bread went on the

bottom shelf and the old bread on the top. We had to eat the old bread first

with the result that we never got to eat fresh bread. It was always at least a

day old and quite dry. Sometimes, out of desperation, we would tunnel into the

fresh bread to get at the soft part which was very palatable. Of course there

would be punishment for this but I guess it was worth it. At lunch we were supposed to take a big bite

of bread and a nibble of cheese. It was difficult to make the cheese last to

the last bite of bread. I don’t remember anything to drink except water. This

was hard to get down but hunger made us finish. I remember being very hungry

after school but no snacks were allowed.

Libero always had a stash of

raisins in a secret hiding place that were his private treat. If one of us

discovered the secret hiding place, we of course helped ourselves to a treat

but we could also use our knowledge as a trading chip for favours from our

siblings. You could trade your turn washing dishes for revealing this secret.

Our dinner table was always

big and full of people. It was the focal

point of the day because that’s when we all came together. The basic number of

people was 11 family members. From time

to time, other people would come to live with us because they had no other

place to live and our basic number would go up to 12 or 13. Somebody or other was always inviting a

friend to eat with us and so it was not unusual to be 15 around the table.

Dinner or supper as we called it, was served at 6 o’clock and if you were late,

too bad. We waited for no one. Libero always presided over these repasts like

the grand master. The family was seated

around the table by order of age from his right except that my mother sat almost

to his left; baby Cinna was between them.

The food was served in big bowls and serving started with Libero and

then was passed around to his left. The

fact that our mother was near the end of the line inhibited anyone from taking

more than their share. We were told how much we could help ourselves to. There

wasn’t an abundance of food and not much variety. Libero did the shopping and the cooking. He

was not an imaginative chef. Beans,

potatoes, cornmeal and pasta were supplemented with tomato sauce, green beans,

peaches and pears, which were preserved in jars to last the winter. My father

cooked liver that resembled shoe leather. We had beans and macaroni often in

the winter. We dare not leave uneaten food in our plates and there were never

any leftovers.

During the summer, we feasted

on the harvest from the very large backyard garden. I remember being very embarrassed when my

mother made me help her pick dandelions, lamb’s quarters, mustard greens and

burdock from a nearby field. We ate baked burdock stems in the summer which

were horribly bitter but they were topped with seasoned breadcrumbs, the only

palatable part of the dish. Nobody else in the neighbourhood ate these foods

and we were thought to be very strange, not only because we picked and ate the

dandelion weed but also there was no other large family around. We were

different for other reasons too. We were

Italian (which made us ‘foreign’) where practically no other Italians lived and

there was always the sound of music coming out of our house. Clemmie had a beautiful voice and she sang

all the time, usually operatic arias which were not familiar to our neighbours.

Because Libero was a

minister, church people and activities were a large part of our lives. We attended church every Sunday. My memory

includes only Silvio, Elvino, Cinna and me escorted by our parents on these

Sunday mornings. We left at about 10 o’clock in the morning dressed in our

‘Sunday Best’ and walked like a procession to Yonge Street to take the

streetcar to 410 College Street at Lippincot where the church was. I disliked

that walk to the corner not only because we had to walk two-by-two in front of

our parents all the while being told to “walk straight with your shoulders

back” but also because I felt we were a curious spectacle on the street. There were also meetings during the week for

young people and choir practice. Some of

us attended Glebe Road United church in our neighbourhood for Sunday school on

Sunday afternoon and perhaps a young people’s group mid-week. Our social life centred mostly on the people

we knew from both churches and a few school friends. There were very few

children on the street to play with.

Music was a large part of our

family life. Libero always seemed to find money to buy records. He had a very

large collection which consisted of complete operas, opera arias, some

symphonies and songs by famous singers. When I was 4 years old and Silvio was

6, our mother taught us to sing a duet from the opera “Il Trovatore” by

Giuseppe Verdi. This is a duet for tenor and soprano, two lovers. We had no

idea of the story and we couldn’t understand Italian. We had learned our parts

by rote. We never had an accompanist. My father would strike a note on the

piano, which was Silvio’s starting note and away we went. We performed in front

of audiences for 3 or 4 years, never knowing what we were doing, but being very

obedient whether we liked it or not. I remember not liking it.

Our family often gathered

around the piano to make music. I would play the piano, Elvino the violin and

everybody sang in spontaneous, improvised harmony. Some of our favourites

included “The Lost Chord”, operatic arias and duets, folk songs, hymns in both

Italian and English and of course Christmas carols in season.

It was not uncommon for

people to own pianos in those days and of course we had one. My mother taught

me the very basic aspects of the keyboard and music reading and rhythm when I

was 4 years old. When I was about 6 years old, my mother decided to use the

money she had saved from her portion of her mother’s sale of her land in

Mottola. My mother, who never had any money of her own nor access to any of the

family income, decided that her savings would be spent on music education. This

is how Silvio and I came to have a piano teacher. His name was Giuseppe Moschetti

and he had just arrived in Canada from Italy where he had been a priest. He

couldn’t honour his celibacy vows and he got married. A defrocked priest wasn’t

too popular in Italy, especially since all he was suited for was playing the

church organ. So he and his wife Dina immigrated to Canada and ended up in

Toronto where he found a protestant church that employed him as their organist.

To supplement his earnings, he had to teach as well. He wasn’t a very good

teacher but Silvio and I flourished nonetheless.

For some reason, probably

because he couldn’t pay his rent, the Moschettis came to live with us. This

meant that we could continue to have lessons after the money ran out, in

exchange for room and board. I believe the lessons were over by the time I was

8 or 9 years old. My mother sang frequently at meetings and church functions.

My first public appearance as an accompanist was in 1940 when I accompanied her

singing an aria from Mozart’s “Magic Flute”. I was 9 years old. For many years,

both Silvio and I often accompanied our mother when she sang in public.

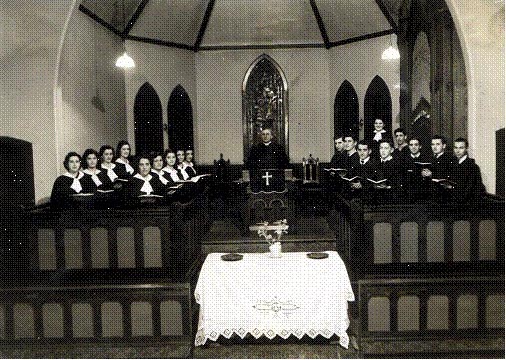

Music was a big part of our

church life as well. The St. Paul’s Italian United Church choir boasted a full

complement of all four parts, soprano, alto, tenor and bass with my mother

leading the soprano section as well as being soloist. Alberindo and Henry were

active in this choir also. Italo was busy with his other vocal commitments and

Livio was a paid boy soprano at another church in town. Livio used to walk a

very long distance to this job to save the streetcar fare but when Pop found

out he was walking, he stopped giving him money for the fare. In fact, Livio

never kept a penny of his earnings, turning them over to Pop and never

receiving so much as a thank you, let alone any material benefit. Olindo isn’t

in these pictures but I think he was in the choir also.

Libero is in

the pulpit, our mother is the first in the front row of the women, Elda

Giovanetti, later to be Alberindo’s wife is the last in the back row and her

sister Quinta is the first in the second row. Alberindo is the farthest in the

front row of men and Henry is the last in the second row beside the organist

Margarite Conforzi.

The

choir, circa 1928-39 dressed in costume, performed around the city and even at

the Canadian National Exhibition, Clemmie at the front left, Quinta Giovanetti

beside her, Elda behind her third form left with my father beside her, and

Alberindo behind Elda, second from left, back row.

Next: Wartime