WARTIME ISSUES

In addition to their church responsibilities, our parents were heavily involved

in the Order Sons of Italy, a benevolent society of Italo-Canadians.

Both parents held high office in the Grand Lodge. This fact was about to turn

our lives upside down.

I remember hearing King

George VI’s radio announcement of the declaration of war against Germany on

September 1, 1939. The atmosphere in our house was tense. The CBC radio station

that carried the 6 o’clock news was on during our dinner every evening and we

had to be absolutely silent because my father had to hear every word. He

followed the progress of the war very closely.

On June 10, 1940, Italy entered the war against Britain and France. It

meant very little to me except in a very vague sense, I knew that we were being

viewed with suspicion.

But on that very day, many Italian Canadians were arrested by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) and interned. Some were members of St. Paul’s congregation, uncle Leonard Frenza was picked up, as was our former piano teacher, Mr. Moschetti as well as many others of our acquaintance. Many also were high officials of the Sons of Italy including our dear friend from Niagara Falls, Mrs. Guagnelli from Niagara Falls who was held with common criminals in the Don Jail. The War Measures Act allowed the RCMP the power to arrest anybody without a charge being laid, hold him or her as long as they wished and without the victim even knowing why. My father was spared from this first sweep of arrests. He suspected that the RCMP informers were fellow Italians who were connected with a Fascist group here in Canada called Il Fascio, which had been trying to infiltrate the Sons of Italy to spread Fascist propaganda. They thought that by having all the officials arrested, the Lodge would cease to function and they might have been right except for my father’s quick actions. He spent the next couple of months reorganizing the structure of the Order so that it could continue to function normally under a crisis situation. He was able to accomplish this before September 7, 1940 when the RCMP showed up at our front door and arrested him. He did however save the Lodge from a very severe setback.

On that day (I was 9 years

old) I was playing outdoors on a small two-wheeled bike that we had somehow

acquired. I saw the unmarked car park in front of our house and two men in

suits enter the house. Being curious, I wanted to go in too but my mother

stopped me at the front door telling me that if I came in, I couldn’t go out

again. She really didn’t want me to be a witness to the events going on inside

the house. I remounted my bike and rode all around the very long block and back

home. When I got back, the car was gone and so was my father. My mother asked

me where I had gone because my father wanted to say good-bye before he went

away. I found out later that the two RCMP officers had searched through the

house, even in my mother’s underwear drawer looking for ‘who knows what’.

Seven-year-old Elvino, who was in the house, grasped

what was going on and hurriedly hid some innocuous Italian language instruction

books to try to protect our parents.

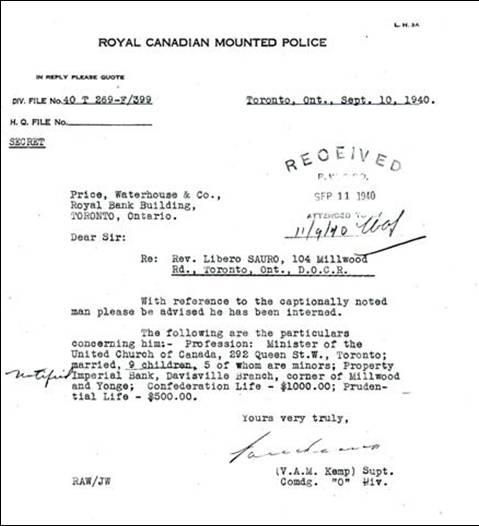

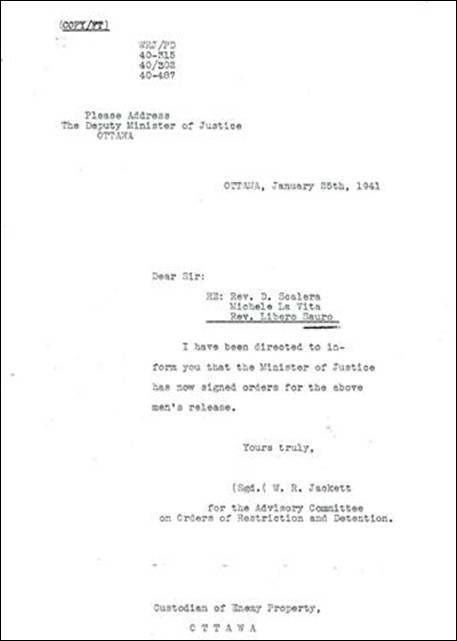

Libero was held at a location in

Toronto that had formerly been the stables for the horses that pulled the T.

Eaton Company delivery wagons, a pretty rough environment. Libero was

eventually sent to Camp Petawawa for the term of his

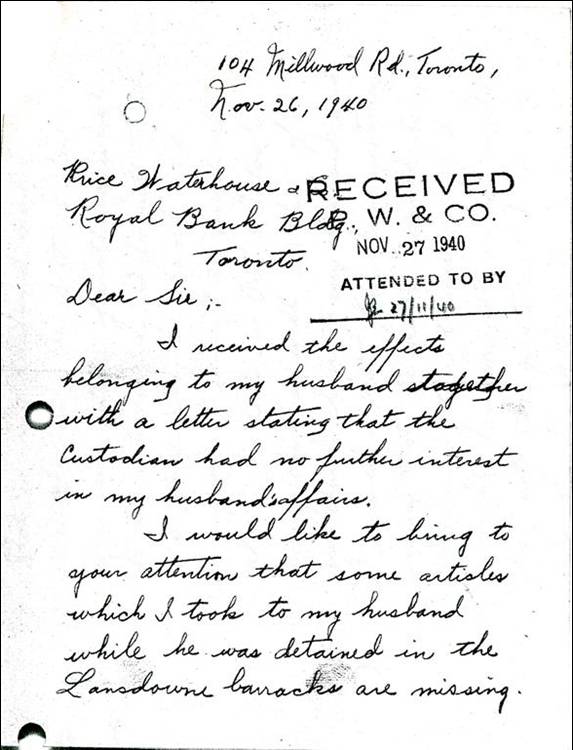

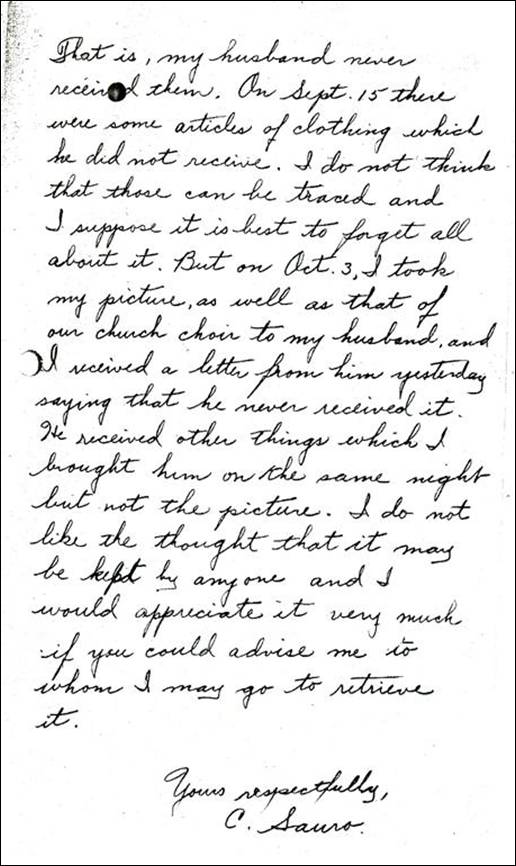

internment. During this time Clemmie was very active

writing letters and working for my father’s release as well as helping to keep

the Lodge functioning. Documents obtained through access to information

procedures are telling. Once interned, the detainee becomes a prisoner of war.

His affairs are taken over by the Custodian of Enemy Property. There can be no

direct contact between the prisoner and is family. All

correspondence had to be channeled through the proper authorities and were censored. The following are some samples of these

documents.

This

is the very date Libero was interned.

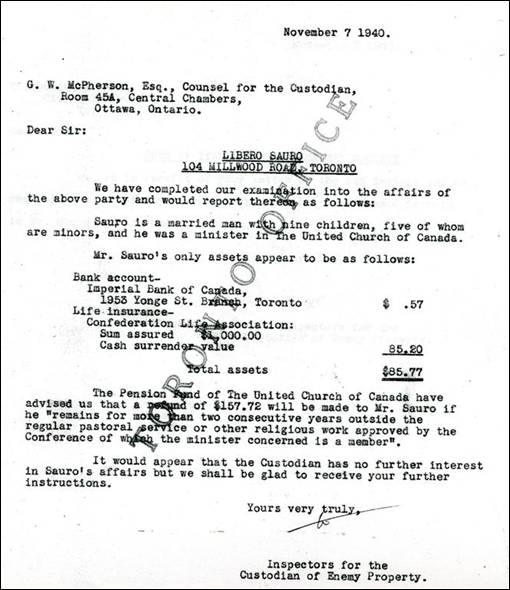

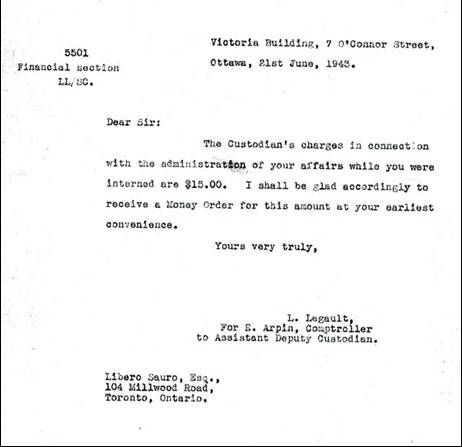

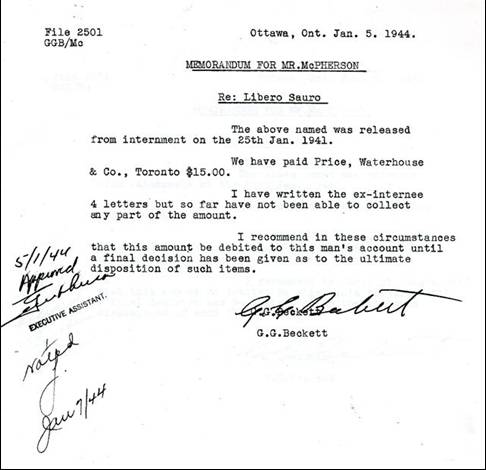

Price

Waterhouse was involved in anything financial with respect to Libero.

It seems that

he was being charged $15.00 for the privilege of having his freedom denied.

I must admit that I secretly

enjoyed life without my father from September 10, 1940 to January 15, 1941 –

the term of his internment. Of about 700 Italians who were interned in Camp Petawawa, some for a few months and others for years, there

was not a single charge laid against any one of them and yet many lost their

businesses and livelihood for which there was never any compensation. We were

lucky in that the Church continued to pay Libero’s

salary while he was interned. When he was released, he continued to work for

the release of the others who were innocently detained.

Although Canada didn’t seem

to be directly threatened by the war, there was nonetheless a chance of

invasion. We had a programme of air raid warning

practice. When we heard the sirens, we were to black out all lights in the

house. A volunteer would then go out in the streets in his area to make sure no

light could be seen coming from any house. These men were members of the ARP,

Air Raid Patrol. My father was asked to do this job. He was given training and

he wore an armband when he went out into the dark night to signify that he was

on Air Raid Patrol. He did this only a very few times before someone on the

street complained that an Italian was given this highly sensitive job to do. We

were treated like enemy aliens. He was quickly relieved of that responsibility.

My father was a naturalized Canadian citizen as was my mother and they were

very loyal Canadians.

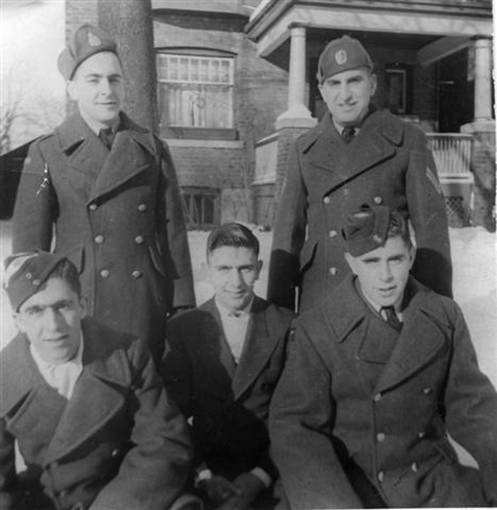

North Toronto Collegiate’s principal at that time was a former army colonel. Every student was involved in cadet training. We were grouped in platoons to march in squadrons around the field and taking the salute, with Colonel Wood in dress uniform at the review stand. In the winter, we marched through the hallways with the salute at the front office. I thought this was great fun.

1942 brought conscription to our door. Any male 20 years or older could expect an official Government letter ordering them to report for military duty. The first to get his call was Alberindo.

He was given basic training and assigned to the Queen’s York Rangers regiment. He was the first of the brothers to be absent from the dinner table every day. He was later to serve in the Intelligence branch of the service.

Italo soon followed joining the Irish Regiment.

When your call came, you had a little time to enlist voluntarily in another branch of the Service, otherwise you were automatically put in the army. By 1943 both Henry and Lindo had joined the Air Force. Both of them were soon to be posted overseas, being based in England. Lindo’s training qualified him to be a navigator but he ended up as ground crew like Henry. The family was rarely united together under the same roof at this time.

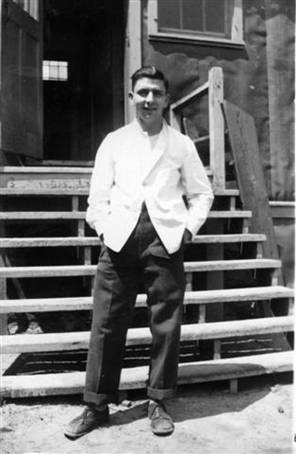

In this picture, there seems to be a wreath in the front window which would make this a Christmas leave, a rare gathering of the whole family. Livio is just 19 and not yet eligible for the draft. On his 20th birthday he too received his official request to report for duty. After his basic training, he was sent to Nova Scotia where he was selected to train as a cook. This training was to be of great value to him in his later civilian life. His working uniform included a white kitchen coat.

Livio standing at the entrance to the mess hall.

With all the older boys away performing their duty the family was much diminished in size.

Cinna on our father’s knee, mother, Silvio, Sylvia and Elvino.

Soon

after he joined the army, Italo met and married Wanda

Willis in 1943. That was the first wedding in our family.

Then

Henry met and married Anna Van Ark in March 1943 before he went overseas.

Anna had a very close relationship with her parents and sisters and brother. Wanda was an only child and we saw a great deal more of her during the time Italo was away. These two women became welcome new members of the family although I don’t think they liked each other very much. They would often visit to share information and letters.

In this picture, a photograph of the absent men was fastened to the speaker cloth of the radio/record player to include them in the gathering of that day. That is the same radio that was constantly tuned to the news to get information not only of the progress of the war but maybe some clue as to what action our missing boys were subject to. It must be said that we heard the opera broadcast from the Metropolitan in New York every Saturday afternoon. We also listened to the radio in the evenings to bring us such entertainments as Bob Hope, Red Skelton, Fred Allen, The Shadow, and a reading of a movie every Monday evening – “Lux presents Hollywood” with Cecil B. DeMille. When the radio wasn’t on, the record player was playing records from our father’s vast collection.

Cinna is on the left of the radio, Sylvia on the

right.

Back

row: Silvio, Wanda, Libero, Clementina,

Livio. Anna, Elvino.

December 1944

Next: More War Issues